Growing a community of creative designers: collaborating and expanding creative design ability

AERA Annual Meeting San Francisco, CA, 2020, Apr 17 - 21

Summary

A mixed-method design informed by activity theory was used to explore student activity and experience within a 15-week undergraduate project-based learning course design in order to gain a firmer understanding of how changes in creative design ability occurred as students designed and delivered projects to solve everyday problems. Learner autonomy, prototyping, psychological safety, tolerance of ambiguity, and community were found to be the main contextual factors that shaped students’ creative design ability. Based on the findings, a model for growing a community of creative designers was proposed and future research questions were formulated. Moscone Center North Roundtable Session 11.

These ideas are proposed to scholars and other stakeholders with interest in providing students with creative and social skills that are predicted to be resistant to computerization (Frey & Osborne, 2017) and therefore likely to serve students well into the future.

Introduction

This paper reports on a larger study that investigated how creative design ability developed for an interdisciplinary group of undergraduate students as they identified, designed, and delivered final projects to solve everyday problems. The research sought to better understand what contextual elements shaped students’ creative design process and to find evidence of creativity and design thinking in students’ developmental process.

Tool exploration and prototyping were the most frequently referenced actions and appeared to grow the course community which reciprocally served to expand prototyping and tool exploration. The community became gradually more pronounced as students took several weeks to choose personally meaningful individual projects and select the design and development tools for their project work. Mid-way in the course, a prototyping community became one of the most predominant contextual factors shaping student development. Data suggested this high degree of learner autonomy instantiated intrinsic motivation structures that supported persistence through challenging project work. The most frequently reported outcomes were increases in creative confidence and new design methodologies. Persistence through challenges was linked to increases in tolerance of ambiguity—the uncertainty inherent to creative design.

Outputs of the study included (a) a theoretical model for growing a community of creative designers and (b) suggestions for future research. The data suggested that development of creative design ability was strongly influenced by community, where tool exploration and prototyping were the predominant actions carried out by students. The contradictions, or challenges students reported were often rooted in the interaction of tool use, prototyping, and community.

Methodology

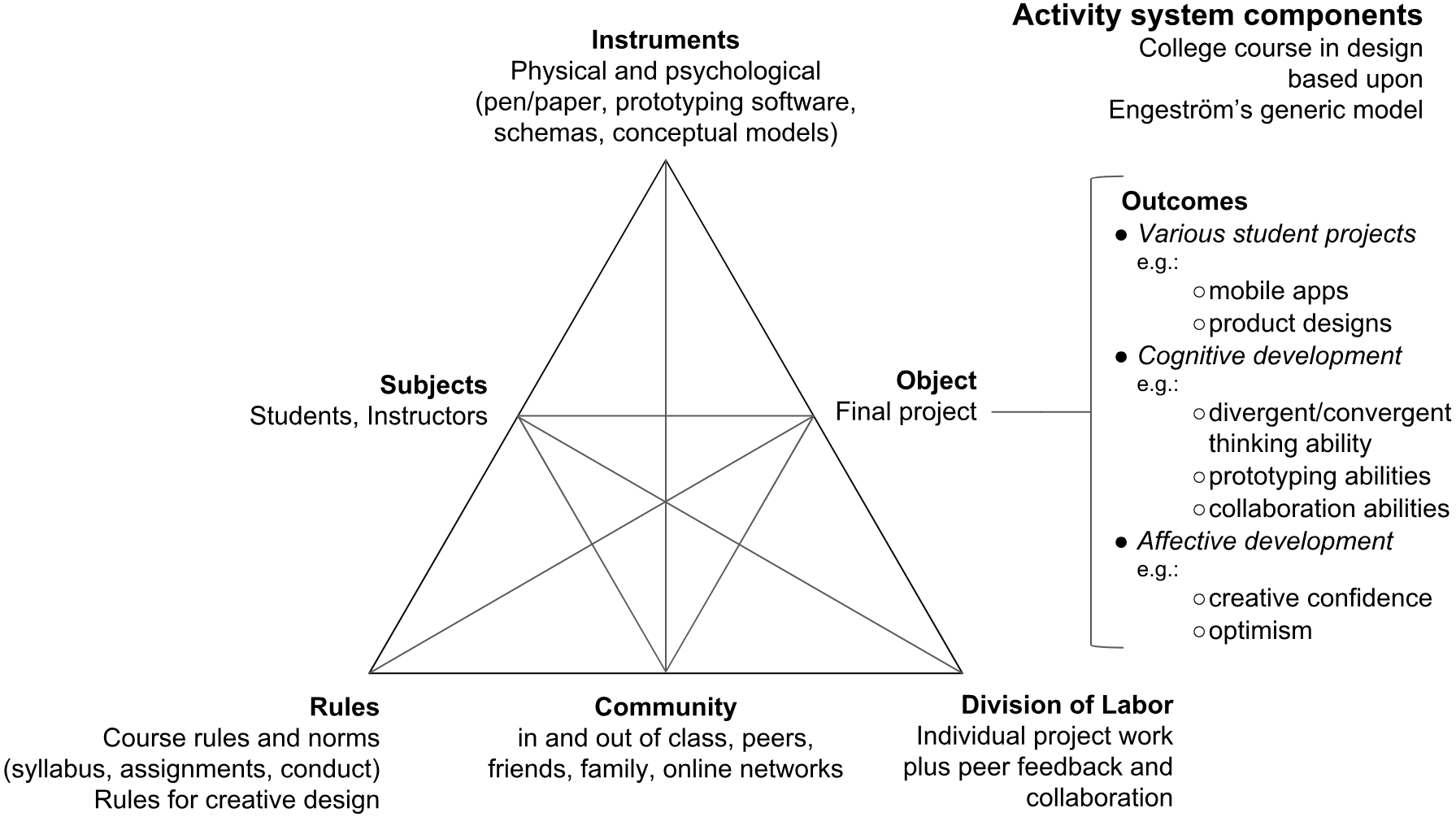

Several methods were used to gather the data for this study, and an exploratory mixed-methods design (Creswell, 2009) was selected. The mixed-methods design afforded a blend of survey, design journal, and interview data within an analytical framework specified by activity theory (Engeström, 2014; Jonassen, 2002) and was informed by the theoretical perspective of social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978) and constructionism (Papert & Harel, 1991.) A depiction of the course as an activity system is shown in Figure 1.

Data was collected via (a) a longitudinal series of student design journals, (b) student interviews, and (c) a design thinking traits survey. The student design journals were a sequence of four entries during weeks three, seven, 13, and 15 and part of students’ normal course work. There was a total of 112 journal entries with an average count of 379 words per entry. The student interviews were conducted during the final weeks of the course. Time duration of the interviews ranged from 16 to 47 minutes with an average duration of 32 minutes. Interview word counts ranged from 3718 to 9246 with an average word count of 6150 words per interview. The survey was a pre-existing one developed by Blizzard et al. (2015) to measure design thinking traits and was comprised of nine item statements scored along a five-point Likert scale. The survey was administered as a pre/post instrument once during the second week of the course and again during the 15th week of the course.

Prior to data analysis a coding scheme was developed. The coding scheme was based on a thematic structure derived from a priori categories identified in the literature and inductively generated categories that emerged during readings of the data. A previous pilot study was used to generate the initial categorical themes for the coding scheme. A literature review of (a) activity theory, (b) creativity, and (c) design/design thinking was used to generate the remainder of the categories.

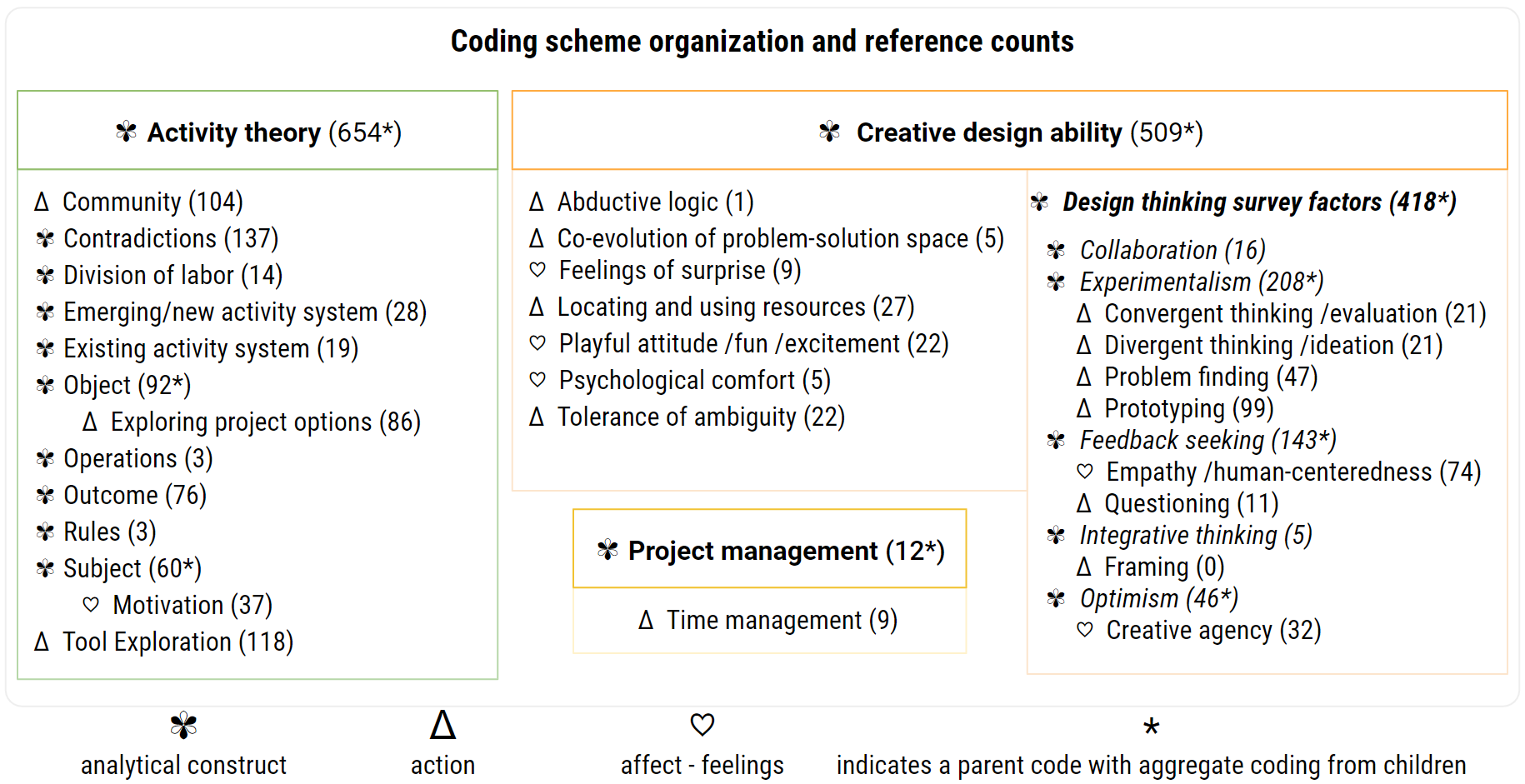

The coding process resulted in 38 codes representing specific actions, affects, and analytical constructs. Thirteen codes were derived from identified themes within the activity theory literature. Fourteen codes were derived from identified themes within the design/design thinking literature. Nine codes were derived from identified themes within the creativity literature. Two codes were derived inductively from the texts.

All codes were categorized as either (a) action (b) affect, or (c) analytical construct. Actions were defined as goal-oriented behaviors carried out in service of the larger objective of the activity system. For example, prototyping was an action carried out in order to realize the object of the activity system, which was to design and deliver a final project. An example of affect was optimism, which may have been conditional to a related action, such as feedback seeking. Analytical constructs were mainly umbrella terms used to organize various codes for subsequent analysis. For example, contradictions was an analytical construct derived from activity theory and used to contain data characterized by significantly challenging moments or phases of project work. Figure 2 below shows the codes and their frequencies in the data.

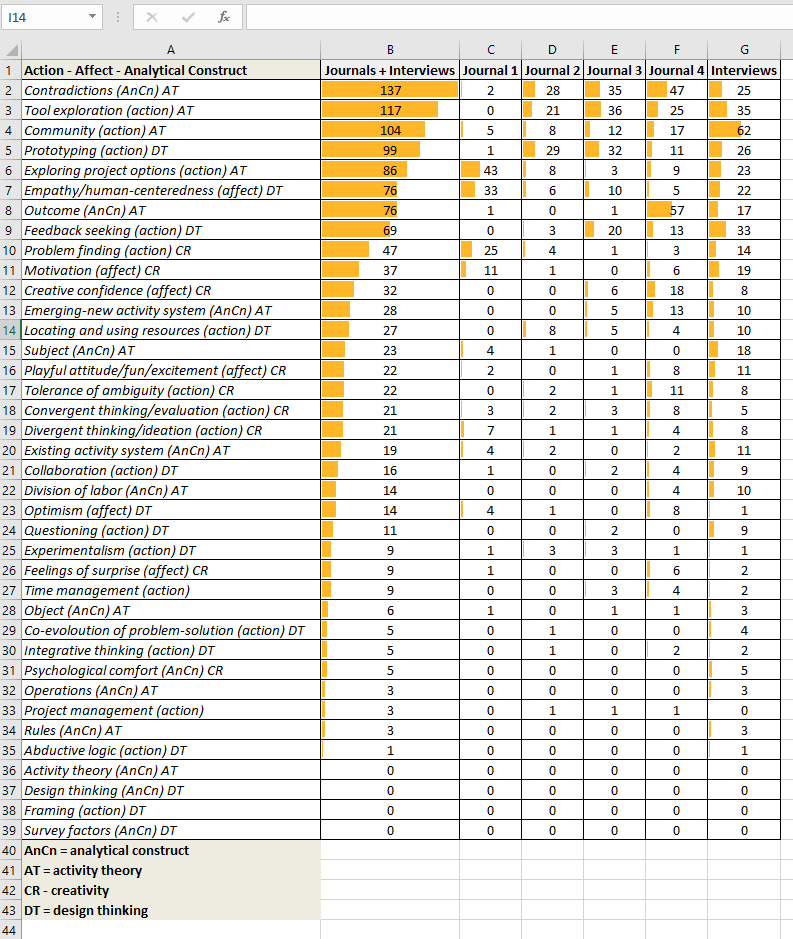

All individual references to codes were counted and rank ordered for the student design journals and the student interviews. Additionally, all references to codes were counted and rank ordered for each of the four sets of design journal entries. The four sets of journal entries were analyzed as a longitudinal time series in order to get a firmer understanding of how students’ creative design ability developed across the length of the course. Rankings of all codes are shown in Figure 3.

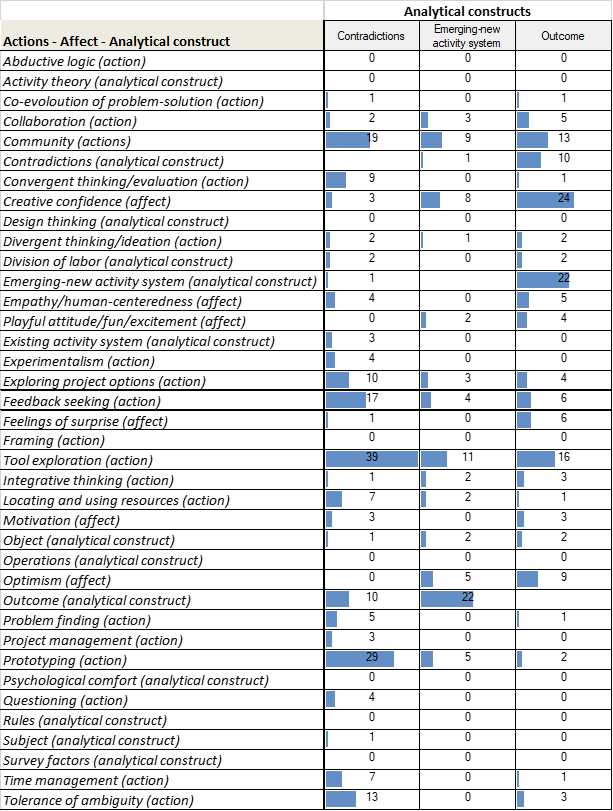

To add depth to the analysis, the most frequently referenced codes and the analytical construct codes were analyzed to see with which other codes they most prominently intersected. Intersecting themes were used to guide further analysis into the dynamics of the activity system. Figure 4 shows rankings for all codes within the three most frequently referenced analytical constructs. Findings from the interview data served to amplify and emphasize findings from the student journal data.

Data analysis and interpretation were guided by the analytical framework of activity theory (Engeström, 2014; Jonassen, 2002), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Mann, 2016), and descriptive statistics (Spatz, 2008). Findings were organized and reported using activity theory (Engeström, 2014) and narrative cognition (Bruner, 1991; Kaufman, 2002; Polkinghorne, 1995).

Findings

Across the student journal and student interview data, the analytical construct of contradictions was the most frequently referenced code. The most frequently referenced codes that intersected with the analytical construct of contradictions were tool exploration, prototyping, and community. Further reading of the data showed that many of the contradictions (i.e. challenges) that students experienced in their course work were instantiated by learning to use new design tools and building prototypes of design ideas. Throughout the student group, community was referenced as a major factor for resolving challenges and moving creative design work forward.

After contradictions, the second, third, and fourth most referenced codes were tool exploration, community, and prototyping. Tool use was the earliest and leading action for students’ project work. Again, community appeared to support students’ tool learning, as they reached out to online communities and received feedback for tool learning from classroom peers and the instructor. Once students’ gained some proficiency with design tools, prototyping became the core action in the course, which was made possible by the course community. Prototyping and community had a reciprocal relationship and simultaneously supported each other’s growth and development.

While prototyping typically led to challenges for students, it also served to resolve those challenges. The action of prototyping appeared to expand the course community, which by mid-way into the course became the most predominant and interconnected theme. Community appeared to be a major hub of student activity and to facilitate much of student development in terms of design ability and the most highly referenced learning outcome, creative confidence. The most frequently referenced code in the interview data was community and underscored the importance of community for the development of creative design ability.

Alongside creativity, students appeared to develop human-centered design methodologies—i.e., new and emerging activity systems for realizing their creative design objectives.

When looking at the intersection of outcomes with all other codes, the codes for creative confidence and emerging-new activity system ranked the highest. New creative abilities and design methodologies were frequently mentioned by students as they reflected on their experience in the course. Most mentions of creative confidence intersected with the code for psychological safety, which was derived from the creativity literature. In this context psychological safety suggested the course environment was conducive to and facilitated creative behaviors. Students reported feelings of creative confidence in themselves, but also wrote and spoke about the creativity of their peers, and how helpful it was to share ideas as a way of iterating and improving their design work. Alongside creativity, students appeared to develop human-centered design methodologies—i.e., new and emerging activity systems for realizing their creative design objectives.

Motivation and tolerance of ambiguity were also prominently linked to student outcomes. It appeared that the high levels of student autonomy in project work afforded students the option to choose project topics that were personally meaningful. Many students reported great challenges with the need to have their own ideas for projects and indicated this kind of freedom was unusual in their experience with school. Likewise, students were given autonomy in tool choice, and this freedom appeared to instantiate authentic learning that was customized to each student’s interest. In turn, student voices evidenced persistence through difficult work and feelings of pride in their accomplishments by the end of the 15 weeks. Motivation was linked to increased ability to manage the uncertainty (Cash & Kreye, 2018) inherent to the creative design process, otherwise known as tolerance of ambiguity.

Discussion

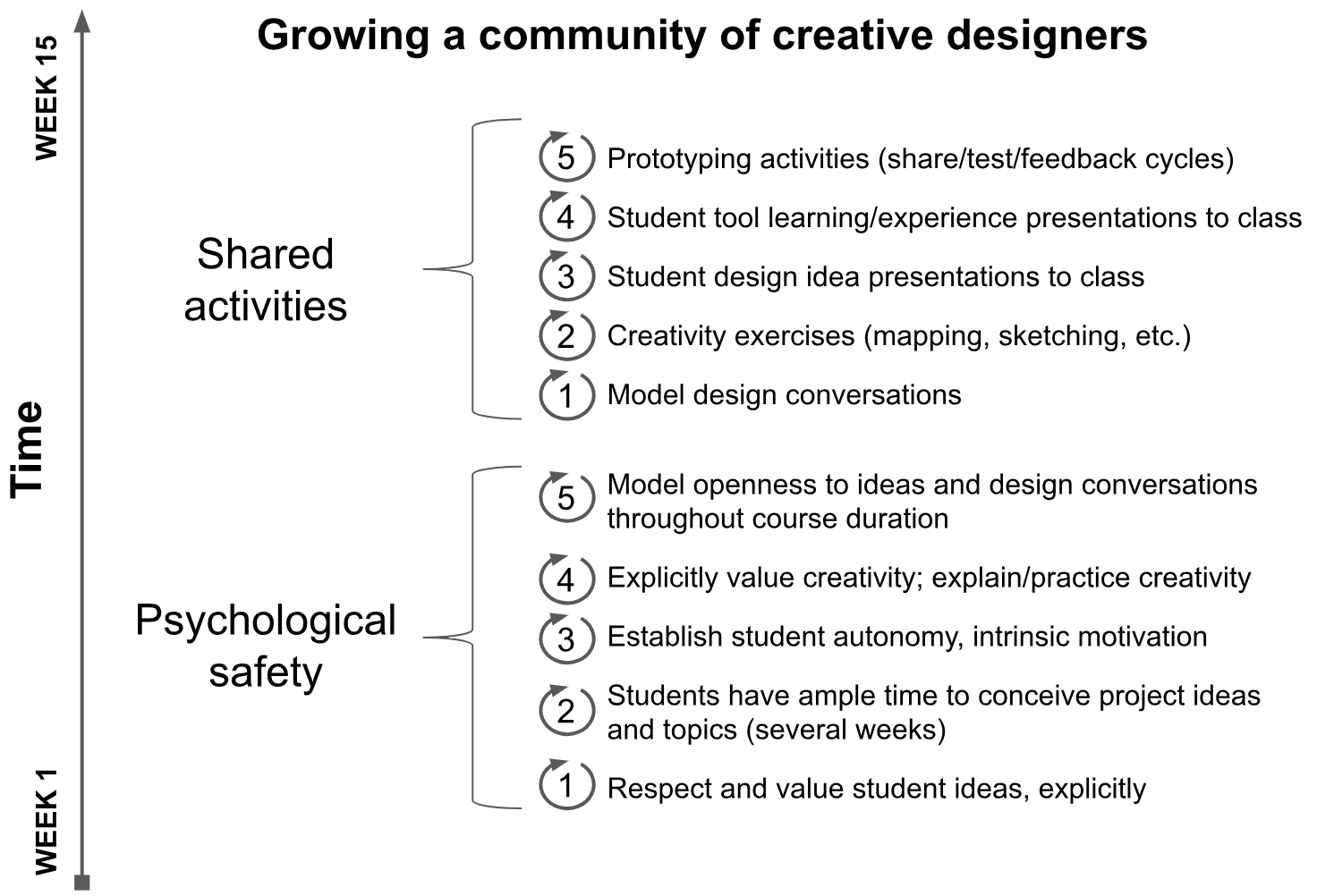

An analysis of the findings led to an interpretation that the combination of psychological safety and shared activities contributed to the establishment and growth of the course community, which the data suggest was influential in shaping students’ creative design ability. Therefore, a model is proposed that emphasizes behaviors that research strongly suggests supports creative behavior. These attitudes and dispositions are used to support a variety of design activities that include peer sharing of ideas, prototyping, creativity exercises, and the modeling of design conversations. It is expected that explicitly valuing student ideas by granting them the autonomy to choose their projects and tools supports motivation structures that sustain project work and support authentic and meaningful learning experiences. Figure 5 suggests guidelines for implementation of the model.

Based on the data from the current study, it is predicted that course communities will strengthen and expand when students are given the time and autonomy to choose personally meaningful projects and are provided a structure that facilitates prototyping actions (Rauth, Köppen, Jobst, & Meinel, 2010) among peers while promoting a prototyping culture characterized by psychological safety (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996; Cramond, 2005; Witt & Beorkrem, 1989.) It would be interesting to explore this prediction further with future research and formative interventions (Sannino, Engeström, & Lemos, 2016.)

This study blended the creativity and design literature with the analytical framework of activity theory to gain firmer understanding of how creative design ability develops for novice designers in a higher education setting. The code book that was generated for this study is intended to be reusable resource for the analysis of similar learning contexts. These ideas are proposed to scholars and other stakeholders with interest in providing students with creative and social skills that are predicted to be resistant to computerization (Frey & Osborne, 2017) and therefore likely to serve students well into the future.

References

- Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154.

- Blizzard, J., Klotz, L., Potvin, G., Hazari, Z., Cribbs, J., & Godwin, A. (2015). Using survey questions to identify and learn more about those who exhibit design thinking traits. Design Studies, 38, 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2015.02.002

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21.

- Cash, P., & Kreye, M. (2018). Exploring uncertainty perception as a driver of design activity. Design Studies, 54, 50–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.10.004

- Cramond, B. (2005). Fostering creativity in gifted students. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Getzels, J. W. (1971). Discovery-oriented behavior and the originality of creative products: A study with artists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 19(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031106

- Engeström, Y. (2014). Learning by expanding (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019

- Huck, S. W. (2008). Reading statistics and research (5th ed.). New York: Pearson.

- Jacobs, J. (2018). Intersections in design thinking and art thinking: Towards interdisciplinary innovation. Creativity. Theories – Research - Applications, 5(1), 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/ctra-2018-0001

- Jonassen, D. H. (2002). Learning as activity. Educational Technology, 42(2), 45–51.

- Kaufman, J. C. (2002). Narrative and paradigmatic thinking styles in creative writing and journalism students. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 36(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2002.tb01064.x

- Kelley, D., & Kelley, T. (2013). The heart of innovation. In Creative confidence: Unleashing the creative potential within us all (pp. 1–11). New York: Crown Business.

- Kienitz, E., Quintin, E.-M., Saggar, M., Bott, N. T., Royalty, A., Hong, D. W.-C., … Reiss, A. L. (2014). Targeted intervention to increase creative capacity and performance: A randomized controlled pilot study. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 13, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.03.002

- Mann, S. (2016). The research interview: Reflective practice and reflexivity in research processes. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1743727X.2018.1425238

- Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. Constructionism, 36(2), 1–11.

- Plattner, H., Meinel, C., & Leifer, L. (2014). Design Thinking Research (L. Leifer, H. Plattner, & C. Meinel, Eds.). Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-40382-3

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103

- Rauth, I., Köppen, E., Jobst, B., & Meinel, C. (2010). Design thinking: An educational model towards creative confidence. DS 66-2: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC 2010), 8. Retrieved from https://www.designsociety.org/publication/30267/Design+Thinking%3A+An+Educational+Model+towards+Creative+Confidence

- Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., & Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(4), 599–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547

- Spatz, C. (2008). Basic statistics: Tales of distributions (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Witt, L. A., & Beorkrem, M. N. (1989). Climate for creative productivity as a predictor of research usefulness and organizational effectiveness in an R&D organization. Creativity Research Journal, 2(1–2), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400418909534298